Mueenuddin’s second book rewards fans’ patience

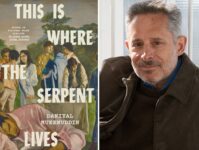

Few authors are less prolific than Daniyal Mueenuddin, author of the novel “This Is Where the Serpent Lives.” Fewer writers still offer such rich rewards for their patient readers. Mueenuddin’s 2009 debut, “In Other Rooms, Other Wonders,” won the Story Prize and was a finalist for both the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. At his debut, Mueenuddin was already in his mid-40s, with an established career as a lawyer and a mango farm in Pakistan. There were rumors of a second book, but nothing appeared for almost 20 years.

The novel opens in an almost Dickensian vein: In the mid-1950s, a 3-year-old boy is found alone in the market of a small town. He has no name, does not know who has left him, and has no possessions besides a pair of new shoes, which he clutches. A food stall proprietor takes him in, gives him the name Bayazid, “Yazid” for short, and watches him grow into a hulking and gregarious young man with many friends among Pakistan’s burgeoning middle and upper classes. Were this a more conventional novel, we might expect that Yazid would uncover the secret of his parentage, win the heart of his upper-class first love, and ascend to the heights of Pakistani society. No such happy events occur; even the shoes, the last key to Yazid’s former identity, are thrown out. Instead, Yazid, after a stint as a smuggler, becomes a chauffeur and majordomo to Colonel Atar, a politician and landowner whose relationship to tenants and employees is repeatedly described as “feudal.”

The second part of this four-part novel, which moves ahead to the late 1980s, concerns a young man, a distant relative of the colonel, who has returned to his family estate after completing an American education. Rustom intends to import his Western values, but his liberalizing intentions run afoul of local realities: A local gang of bravos is damaging his property, stealing his equipment, and attacking his servants. Rustom reluctantly summons the gangster family that has long done dirty work for him. The toughs subdue Rustom’s foes with a show of force (“Someone said they drove the tractor over the boy’s knees”), but little is resolved. The next piece of the novel concerns Colonel Atar’s two sons and a romantic rivalry kindled in the snows of Dartmouth, N.H., and finally resolved on a Punjabi glacier.

The final section, which shares its title with the novel, is longer than the first three put together. It follows the rise and fall of Saqib, a gardener’s son born in 1989 whose family is in service to the Atars. The colonel’s son Hisham and his wife Shahnaz take a shine to him, as does an aging Zayid.

Saqib loves, admires, and envies his employers, and in the heady atmosphere of the late 2010s, Saqib has both ambitions and expectations that Zayid never countenanced. The chauffeur pines for an unattainable woman; Saqib orchestrates a marriage above his station. Zayid drops his masters at the airport; Saqib hopes to fly away. When Hisham and Shahnaz assign him to an innovative farming project, Saqib senses the chance for dishonest advancement. A little graft is expected of high-ranking servants; as the narrator wryly observes, “the system did not just tolerate theft on a small scale but assumed it.” Saqib, in his bid to join the ranks of great men, overdoes it. His genuine sense of guilt turns out to be the least of his worries.

As the plot summary suggests, “This Is Where the Serpent Lives” is a story writer’s novel. Any individual section could stand alone, and the first two parts indeed appeared as separate stories in The New Yorker. The component pieces are linked by theme more than plot, and Mueenuddin frequently abandons his characters at moments of ambivalent possibility. Elisions abound: Ten years of Zayid’s life disappear into a few paragraphs; narrator and protagonist alike are so caught up in Saqib’s scheme that the birth of his first child is mentioned as an aside. Mueenuddin can do dramatic set pieces — murder, police torture, a wife begging for mercy for her husband — but he finds more significance in quiet moments of reflection, rationalization, and self-deception.

“This Is Where the Serpent Lives” is, in part, a novel about class, and the way in which it damages “high” and “low” alike. Zayid and Saqib are men of different eras and similar potential; neither manages to rise very far. The wealthy characters may receive Ivy League educations and shop in London boutiques, they may hold ambassadorships or drive a Mercedes, but once they come to their farmstead or city compound, they find themselves just as implicated in traditional culture as their servants and laborers. Even when they want to be egalitarian, Rustom, Hisham, and Shahnaz still yield to feudal tradition. In Hisham’s last appearance in the novel, this urbane man, with “the largest and most encouraging laugh in all Lahore,” kicks a prostrate servant who has offended him before turning over another to the venal local police for an extrajudicial beating. Mueenuddin, who comes from a similar elite Pakistani background, empathizes without exonerating. The characters repeat old, even ancient patterns: Saqib’s expulsion from the Atars’ paradise hinges on his desire for an Apple iPhone. That Mueenuddin makes this plot development seem natural rather than heavy-handed is a testament to his gifts.

“This Is Where the Serpent Lives” maps an entire society in flux over six decades while presenting half a dozen portraits of contradictory, sympathetic, flawed, and utterly believable individuals. This subtle, wide-ranging, and enthralling novel makes some demands of its readers, but repays them in full.

THIS IS WHERE THE SERPENT LIVES

By Daniyal Mueenuddin

Knopf, 368 pages, $29

Matthew Keeley is a freelance writer who has written for The Washington Post and the Los Angeles Review of Books.